LEGO Fabuland

Two children found a termite nest on their father’s farm. The oldest child became fascinated by the structures the termites created, and spent many hours playing, replicating them in drawings and models. The younger child played a different game, visiting the termite nest daily, leaving cake crumbs and leaves for the small creatures to use. As an adult, the oldest child designed aqueducts that brought clean water to her city, and was rewarded by the king for this important work. The youngest child became a philanthropist establishing almshouses for the very poorest people, and was similarly rewarded. The moral: there are many ways to play, and each may lead to its own good.

This little attempt at a fable could be taken as an allegory for the way we think about the types of play LEGO bricks afford. Unconsciously we attribute to LEGO certain types of play, which culturally have been considered consonant with the practical problem solving games of engineering[i]. And whilst there is no doubt that it provides a fantastic springboard for this way of thinking, there are indeed other ways of playing with bricks some of which require an active participation with the worlds they create.

One of the outcomes of this intentional interaction is that worlds built from LEGO bricks create a stage for a type of play that performatively encourages storytelling. For an art form that predominately deals with static 3D models, the fact that it has become so conducive to narrative exposition is something that requires deeper investigation.

Rewind some thirty-nine years to the late 1970s and the advent of the now iconic mini-figure. This inspirational design profoundly changed the company’s thinking. By introducing characters to the range of elements sold as kits it altered the way in which LEGO bricks would and could be played with. Crucially adding faces and articulation to the figures, allowed them to be more than the place-holders for characterisation that the earlier faceless figures had been.

LEGO mini-figures on the cover of the 1978 catalogue

Of course figurative elements had existed long before the creation of the mini-figure. There are brick built figures aplenty, like those found in the Moon Lander and the Maxi Figures found in the Homemaker sets. However all of these cases still needed to be built and remained more of an adjunct to the model building process. Whilst the maxi figures featured elephant trunk like articulation, their clothes and bodies were still built from bricks; actually playing with them proved more problematic than one would expect (the three-year old me could attest to this).

LEGO Maxi-Figures

The mini-figure on the other hand in no way attempts to be a figure built from LEGO bricks. They are discrete entities, designed as a stand-alone system. Yes, they do adhere to the broad logic of interchangeability, with their studded heads and hats and variety of trousers, but ultimately there is really only one – although that rule is often broken – way to build a mini-figure.

The characters’ success came from the ability of this new system to interact with the standard brick. The anti-studded bottoms and feet of the mini-figure meant that its narrative and character driven system of play could intersect seamlessly with the building and model making potential of the traditional range of elements. And in reverse, the clip logic of the mini-figure hand introduced new connective elements to the standard range of pieces.

Sets that now contained a range of mini-figures altered the established idea of LEGO as a model kit. Whilst models were still built, they were now constructed for the reason of providing a world in which the mini-figures’ stories could be told. And a new realm of play between building and story telling was born.

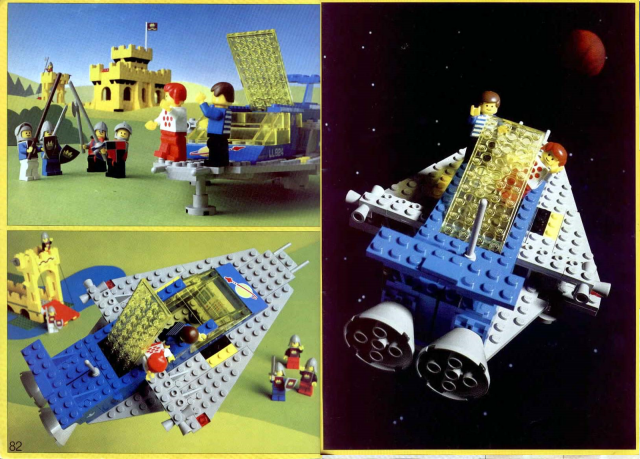

Intuitively children grasped the concept that you could tell stories with LEGO bricks. The question ‘why build?’ had attained a new dimension and arguably a new audience. The LEGO company also understood the value of this new approach, and explored it in the Idea Book published in 1980. More than just a collection of inspiring models to build, the book told the story of two archetypal mini-figures, and their journey across the then current LEGO themes. From town to castle by way of outer space these two heroes offered a reason to build. The replication of the real sacrificed in favour of a fantastical world of adventure.

LEGO Ideas Book 1980

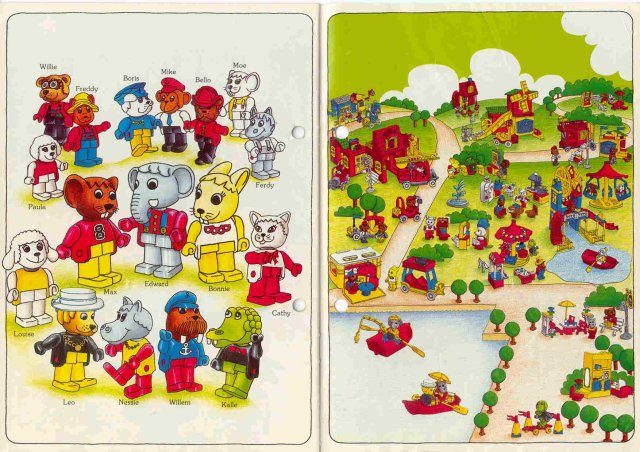

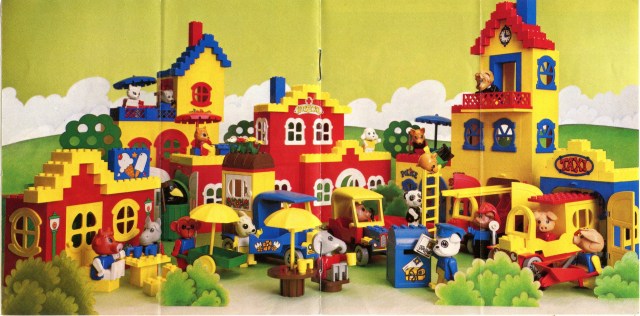

But the mini-figure was just the first step into these new realms of play that aligned with narrative thinking. Following quickly on the heels of the mini-figure LEGO developed the Fabuland range of sets. Taking the aspects of characterisation that the mini-figure had opened, these sets saw the creation of an anthropomorphic group of friends. The mainly alliteratively named Charlie Cat, Robby Rabbit, Ernie Elephant and others, living together within the eponymous Fabuland, put story telling play, and the play of the fable, at the centre of the LEGO experience.

Fabuland

The range has garnered both advocates[ii] and critical response over the years. On the negative side, it is seen as reducing the LEGO building experience, in its employment of large pre-fabricated pieces, such as windows and scooters, which required no building. It represented for these critics a ‘dumbing-down’ or ‘juniorisation’[iii] of the LEGO building experience. Of course the sets were designed for the younger range of the company’s audience, and the simplicity of the building experience offered, stood in contrast to the tastes and needs of the advanced builders who made up the vast majority of the critics At the other end of the spectrum, the charming design ethos of the characters combined with the development of many new and ironically multi-use elements made the series a fascinating addition to the LEGO catalogue.

It could be argued that the critics had missed the point; that a deliberate choice had been made by the LEGO Group with regard to Fabuland’s range of elements. These constituted a new system of play, in much the same way that the mini-figure had. The notion that the sets were created to facilitate model making was replaced by the need to foster story telling. Quickly utilisable objects and units such as windows and doors provided the best way of generating narrative play.

As with the mini-figure, the success of the venture stemmed from the retention of universal connectivity, which allowed Fabuland to adapt to both standard LEGO bricks and DUPLO bricks. In this sense its system of play remained essentially open to the more recognisable LEGO building experiences, at both the younger and more advanced ends of the company’s demographic.

This freedom has seen a small but continuing engagement with the theme from the adult building community. Many took the naïve forms, and accentuated their architectural tropes to create a unique and knowingly twee alternative reality. Those skills that had been developed by the architectural and castle builders found new fertile territory in these works. The advancement in techniques undermining the perception that the simplicity of building must essentially tie the range to a younger audience. Builders like Tikitikitembo[iv] prove the point when they take the fable element to its literal conclusion, using Fabuland combined with more advanced building techniques to recreate traditional children’s tales like The Three Little Pigs. The anthropomorphic figures continuing a long tradition that uses the characteristics of the animal to explore our human foibles.

Three Little Pigs by Tikitikitembo

So whilst the extension of the Fabuland theme by the enthusiasts explored the aesthetic terrain of the theme, by proxy they also continued to develop its affinity for story telling. And not just any story telling, the animals that LEGO created being direct descendents of Aesop’s own creations. The result a fusing of the problem solving and creative building experiences with the narrative devices of the fable

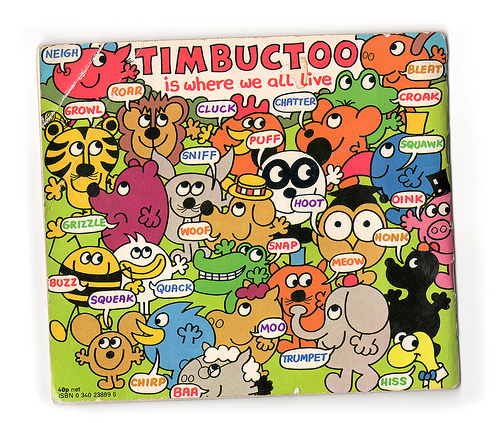

This return to the fable is something of a theme in children’s literary of the late 70s. Fabuland mirrored the terrain writers like Roger Hargreaves and his Mr Men books, and the lesser-known anthropomorphic Timbuctoo[v] series, had taken in embracing the fable and its ability to tell allegorical tales.

Roger Hargreaves lesser known Timbuctoo series

Following the transition made by Hargreaves to Television, so Fabuland became LEGO’s first interdisciplinary foray. Edward and Friends[vi] the Fabuland show, produced by Film Fair, the same company responsible for cult classics like The Wombles and the 1970s Paddington television series, shared the Mr Mens’ sense of storytelling. Each of the animal characters explored moral problems through simple narrative dilemmas. Fabuland in its translation from building toy, to more traditional narrative forms such as television and even a range of associated books, revealed just how versatile an aesthetic LEGO was for telling stories.

This resurgence of fable like stories in children’s literature and television can be tied to a larger trend in literary theory. In 1967 the literary theorist Robert Scholes had written his seminal text The Fabulators[vii], which was followed in 1979 by a second volume on the theme entitled Fabulation and Metafiction[viii]. Scholes’ considers a range of novelists, such as Borges, Durrell, Pynchon and Barth, as actively choosing to create worlds that whilst referencing the real operated as alternative fabulatory constructs. This shift away from a concrete notion of the real, allowing a fresh way of dealing with ethical and social problems aside from the realist literary movements. He writes, “modern fabulation, like the ancient fabling of Aesop, tends away from direct representation of the surface of reality but returns toward actual human life by way of ethically controlled fantasy”[ix]. The fabulator’s narrative does not seek to show the conflicts between the individual and society, rather the struggle between a world and the ideas, dogmas and conditions that allow it to exist.

The genre of science fiction – another theme the LEGO Group and popular culture were embracing in the late 70’s – benefited from this theory. It also reflected a changing public taste, where the modern myth would be played out in the alternative realities of other futures, galaxies far, far away and romatacised pasts. In these self-contained mini-verses big ideas regarding what it means to be human and their ethical grounds could be explored as concepts.

The LEGO Group’s embracing of play that revolved around the creation of fabulous other worlds replicated this cultural movement. Children were being encouraged to explore their world through the imaginative creation of their own fantastical constructions and characters. And in turn were being asked to think ethically about what constitutes a world, and what those parameters mean for its inhabitants.

So far my exploration of the LEGO Group’s development of the narrative potential in their sets has spoken of the theme purely in the context of children’s play. That narratives are discovered in bricks through the children’s act of playing and telling stories. And whilst this may be a place where many of the adult building community first started to explore narrative devices, the variety and complexity of their work now challenges the idea that play is a purely childish aspect of the LEGO art form; something that serious builders and artists outgrow.

To understand the importance of the role of play in a LEGO creation’s ability to tell stories it helps to think how it differs from traditional art forms. In one sense you might think that LEGO artworks function as illustrative counterparts to narrative pieces. The number of LEGO builds that realise a scene from a film or book would seem to support this. The 2013 VirtuaLUG[x] collaboration, which saw the collective recreate in diorama form the story of The Wizard of Oz being a case in point[xi]. Does this piece only work if you know the story of The Wizard of Oz as a film or novel? The answer is emphatically no. Although an illustration, if one did not know the famous story, through its set-up it provides the components to allow one to link scenes together, to create a story – it just might not be the story that inspired its build.

VirtuaLUG The Wizard of Oz

This is the crux of the matter. To tell the story present in the LEGO artwork, the audience has to play with the aspects of the build. Inventing and playing with features of the creation, making creative and imaginative connections – telling new stories of their own. Like the child who tells stories with the Fabuland world they have made, the audience who view a LEGO artwork, has to use those same skills, effectively remembering how to play and engage with an alternative world. Play is the active component in this dialectic between static 3D creation and the temporal story. Play makes every spectator of the narrative LEGO artwork an author too.

To anyone who has spent time studying painting this revelation tells them nothing new. For example the allegorical painting of the Middle Ages require the active participation of the viewer to disclose both narrative and meaning. However, narratives in LEGO further increase its audience’s intentional interaction beyond the two-dimensional image. A LEGO creation that tells a story is never finished; the interlocking pieces and the placement of the characters, always remain open to reconfiguration, rebuilding as is the want with LEGO elements’ intrinsic malleability.

Taking the premise Mark Currie puts forward in his book on narrative time, simply titled About Time[xii], there is a conflict in the structure of a written narrative, and I would argue a similar issue in the narratives produced in film. That the moment of reading, where we find ourselves part way through a story, not knowing what awaits its characters in the future, is an illusion of a future possibility; it is already structured as part of a finished whole – the story is already written. Even the author who writes, and begins with open possibilities, must eventually relinquish this privileged position and commit their story to the block time order of a narrative. However, should we concede that the audience of a LEGO art work which presents narrative possibilities, is not a reader, but already a potential builder, and re-builder of the work, how does this change the narrative scenario to that found when reading a novel?

The stories that LEGO artworks offer do so not through the traditional conditions of recording a sequence of events and happenings, nor through the active interpretation of events that have been established. They begin by asking its audience to play with them. To take on an intentional role, to tell stories with the figures and pieces present. When we look at a LEGO artwork, which implies narrative, we begin by seeing all the physical connections that can be made, where figure may stand, where houses, castles and buildings may be restructured, and we begin to play and imagine what might be.

In the more traditional illustrative pieces of LEGO art, this capacity to play remains purely cognitive. We become virtual builders. The skill of the LEGO artist in these cases is to create a world that induces imaginative play and shows paths and associations of bricks and characters that an audience finds inspiring to think about. As soon you find yourself saying “where are those knights going”, or “what cargo is being loaded onto that spaceship”, and start to answer your own question, then you are initiating a playful activation of the nascent story unspoken in every creation.

This focus on generating narrative has become a core part of the LEGO experience, no more so than in the official LEGO video games. It might seem surprising that the actual act of building is so minimally represented in these games, that is until you understand them as forays into the art of play driven storytelling. The analogue between LEGO building and the video game comes from the requirement that worlds are built so as to be explored and played within.

The LEGO video game presents these worlds made and ready to explore. However, as is the constant struggle in video games, the dilemma between narrative exposition and compliance to the requirements of the game limits the range of stories that can be told. So whilst the LEGO video games returns a tangible intentional quality to story telling, it does so at a cost, through the adherence of the narrative to the game’s rules; to competition and problem solving.

LEGO City Undercover video game

Perhaps the video game can find some answer to its genre specific conflict in LEGO’s narrative potential. The assumption regarding the generation of a narrative from an artist’s LEGO creation, is that these works are created, finished and only virtually engaged with. If the LEGO builds of adults however reclaim the open play of childhood, where would this lead the narrative potential of the medium? What would happen if an audience wasn’t only asked to look at a build, but participate, play, change and move components around?

This would extend the argument that Scholes’ has made with regard to fabulation. The other worlds built from LEGO bricks, unlike their literary counterparts, don’t simply present the ideals and concepts in separation ready for investigation, they offer the possibility of changing altering and setting up new ideas and intentions beyond those that the original builder perceived. Playing with a world, with the fluidity of an ancient god, puts not only the mini-figure back into the playful hand of the adult, but also the ethical responsibility for the stories they tell with them. And here we end back at the fable that started this invesigation, with child who played with the termites as a benevolent deity, and subsequently learned the value of caring for their world.

Endnotes

[i] See Sir Harry Kroto’s infamous comments as recorded in The Telegraph article ‘Why Britain needs more Meccano and less LEGO’, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1333215/Why-Britain-needs-more-Meccano-and-less-Lego.html (accessed 30 May 2015).

[ii] See the Fabuland Builders Guild webpage, http://www.eurobricks.com/forum/index.php?showtopic=17396 (accessed 30 May 2015).

[iii] According to Brickwiki, “Juniorization is a term used by Adult Fans of LEGO to both describe and criticize the inclusion of a few highly specialized elements in sets instead of already existing elements that could be assembled into the same configuration.”

http://www.brickwiki.info/wiki/Juniorization (accessed 30 May 2015).

[iv] See Tikitikitembo’s Flickr stream https://www.flickr.com/photos/64693712@N05/.

[v] Reference to add.

[vi] Links to the Edward and Friends episodes can be found here, http://lego.wikia.com/wiki/Edward_and_Friends.

[vii] Robert, Scholes, The Fabulators, Oxford University Press, Oxford (1969)

[viii] Robert, Scholes, Fabulation and MetafictionUniversity of Illinois Press, Chicago/London (1979)

[ix] Ibid, p.3

[x] See the Virtualug homepage, http://www.virtualug.org/.

[xi] See the Brothers Brick review of the collaboration, http://www.brothers-brick.com/2013/07/09/virtualugs-wizard-of-oz-diorama-will-knock-off-your-ruby-slippers/.

[xii] Mark Currie, About Time: Narrative, Fiction and the Philosophy of Time, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh (2010)

Thanks Geoff. I’ve often thought that even the intention that something built might be played with constitutes this idea. For example when I build classic space models, I consider play factors as important as style.

LikeLiked by 1 person