Is there a right way to build with Lego? Doesn’t this question stand in stark contrast to the creative ethos at the heart of the Lego experience? You might well think so, but it is precisely this question that motivates recent critiques about the way Lego has changed, since the launch of its initial range of basic bricks. New themes, film tie-ins and a host of specialised pieces are all supposedly detracting from Lego’s creative potential.

Justin Parkinson provocatively titled his recent article for the BBC ‘Has the imagination disappeared from Lego?’[i] The report summarised some of the common misconceptions expressed about Lego’s recent developments, drawing together from various sources the arguments against the changes the company has implemented. But do these arguments hold up, is Lego now promoting a toy that falls somewhere short of an original ‘authentic’ way of building? I don’t believe so, and will show in each case why Lego continues to propagate our children’s and our imagination.

So what are the cases for the demise of Lego’s creative and imaginative potential? Loosely speaking Parkinson breaks things down to three key points:

- The instructions provided in current Lego sets dictate single builds, rather than offering a child the opportunity to explore with their own imagination;

- Specialised pieces, that have one specific use, limit the number of creative possibilities open to the child;

- Lego is too simplistic and doesn’t help a child develop their building towards an ideal form, primarily with engineering and scientific application.

Starting with the principle that single sets of instructions hamper creativity, Parkinson cites blogger Chris Swan, who is recorded as saying: ‘Single-outcome sets encourage preservation rather than destruction, and sadly that makes them less useful, less educational (and, in my opinion, less fun)’[ii]. And on this out of context quote[iii] hangs the whole of Parkinson’s case. If you take the time to read Swan’s article, there is a more nuanced position. He in fact argues that children find it harder to dismantle Lego, and engage in creative re-imaginations of the bricks, if they are channeled towards models to collect and keep.

Swan is fundamentally wrong however, when he suggests that there is a preferred or more authentic way of building with Lego. Consider the irony in the statement he makes, which suggests the best way to build is to avoid the rules and work from intuitive imagination and individual creative application, when it in turn becomes a rule by which to establish value judgments about the types of ways a child can interact with Lego.

For many of us who build with Lego, the creative experience Swan explains mirrors our own enjoyment of the medium, and this gives it an unfounded rhetorical conviction; unquestionable in the Lego community. But this isn’t the only way to build, and other ways, including sticking to the instructions, are not necessarily, less fun, or less imaginative. Swan exemplifies the type of morally high-minded adult validation of Lego, that sees it as best understood as a way of educating a child, developing certain transferable skills, and activating a free creative spirit. Whilst Lego has the potential to do all this, it should not be reduced to this alone.

Building from instructions has been part of the Lego experience from its inception, and is a core part of its imaginative potential. If we were talking about any other creative medium, the need to develop skills through instruction or imitation would be taken as a given. For example, imagine trying to compose music without first learning how to play an instrument, read music and practice scales. Unless you have a prodigious talent, it would be folly to turn your back on this wealth of experience. The lessons learnt by following the instructions in a Lego set, develop these skills in one’s own building.

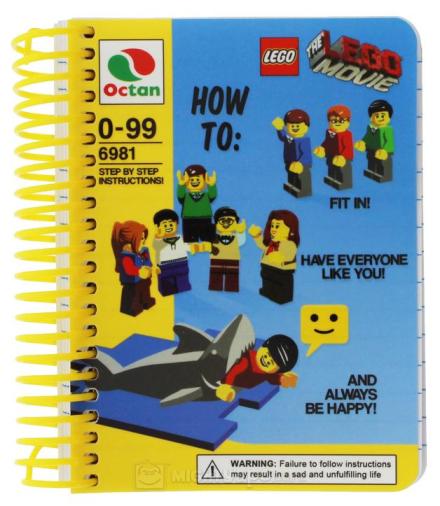

Take Emmet the everyman construction worker from the Lego Movie[iv], who carries latent master builder skills, through his long-term adherence to the instructions. His construction mech, realised at the film’s finale is an expression of all those learnt techniques redeployed. And behind this narrative we have Will Ferrel’s son, who is implied to have played with his father’s Lego display according to the rules set for him, and only once his imagined narrative required new creations, does he find the courage to build his own way. Just like Emmet’s complete submission to Lord Business’s hegemony, his skill is based on the knowledge he had acquired from his interaction with his father’s world. As the film notes Lord Business was the greatest master builder after all.

City building Emmet’s way.

This example exposes Swan’s child, who builds a Lego set and then methodically destroys it, as an idealised fantasy. Possibly this occurs from a filtering we all have, as to how we ‘think’ we played with Lego in our own childhood. How quickly we forget that Lego lets a child build a toy: racing cars to be raced, houses to be lived in, spaceships to explore distant galaxies with. The games in which the child engages in, is often the missing catalyst (which Swan misses) for inspired creation. And you need to build and keep sets to create this arena for inspired play. Rather than imagine the perfect creatively driven child and a set of abstract bricks, how many of us in fact relied on the themes of more experienced and better builders than ourselves (normally professional Lego designers) to step forward with our own imaginative endeavors. Some of us as adults still collect and build those classic sets of our childhood to display, but then add to them with something of our own. Jon Blackford’s wonderful Classic Space display[v] shows this principle in action. A complete set of original built sets surrounding a fantastic new creation of his own.

Swan’s further assumption in his article is that Lego as a company is moving towards a range dominated by single outcome sets. This is simply not true. Lego in reality has consistently diversified its types of building experiences. Whilst core areas such as Lego City, Star Wars and Lego Friends do indeed present single outcomes sets, they are supplemented by the 3 in 1 Creator sets, Technic and as of last year the highly successful Mixels range, all of which encourage multiple builds from individual sets. Taking Mixels as a case study, here is a toy that seems to refute Swan’s perception. Its name itself inspires the idea of mixing and rebuilding. The urge to collect small pocket-money sets, off-set against a principle that smaller sets can be broken down and combined with others to make ever bigger and stranger creatures.

A deeper argument though, is not simply that there is a diversification of building styles and options being offered by Lego, which necessarily would seem to suggest an increase in the ways in which our imagination is being activated, but that the purported dictatorial single outcome set is not the negative anti-creative experience it is portrayed as. Taking the extreme examples of this type of build, the large modular town sets, the architectural building range or Star Wars Ultimate Collector Series, there are a number of positive things to be said. As the complexity of these models increase, so do the techniques required to build them. As a learning experience these sets share a huge amount of knowledge with a novice builder. Far from being a lesser educational experience to that of free invention, they simply offer a different one.

This still hasn’t answered Swan’s main claim though that single outcome sets reduce imaginative potential. The problem arises from a common misconception that Lego is a pure participatory experience. One has an authentic experience of Lego when one is building; reflection on that which is created is of a lesser order. In my last article where I built a case for Lego art[vi], I challenged the lack of analysis given to the act of viewing and responding to Lego creations. My conclusion being that Lego activates the imagination by simultaneously revealing to the spectator its built and un-built state. So if a child builds a set that inspires reflection and wonder of this kind, and this relationship is one they seek to maintain, is it fair to consider this relationship a negative or inauthentic one?

When we look at other creative mediums, we almost never distinguish levels of authenticity between making and responding to work. If you listen to a piece of music and do not immediately decide to respond by composing music of your own, would this then make your relation to music an inauthentic one. If you read a novel, and are not moved to write, has the experience diminished your imaginative experience of the work? As such, it is possible to build a Lego set from the instructions and not feel a need to build something of your own, and this too is a valid experience.

The problem Swan exposes is that we often try to pigeonhole what good play is, and consequently how imagination should be employed. When we try to reduce Lego to an ideal type of engagement, we miss so much of what it can be (in this case a source of wonder and speculation). Lego as a company has grasped this and is offering an ever widening range of experiences to its audiences, including that of collection and reflection. Those commentators who want to step back in time, put the genie back in the bottle and deny these new experiences for a perceived more authentic earlier one, are doing anything other than defending Lego’s imaginative potential.

The second case given by Parkinson involves the use of specialised pieces. Like the case for single outcome sets, this issue relates to the reduction of authentic building opportunities, created this time by the introduction of new elements. The argument is presented here through a historical perspective, that Lego in the early 2000’s got things wrong by producing sets with too many specialised pieces, which led to ‘instant gratification building’. Lego realised its mistake and has since rectified the balance. Quoting David Gauntlett’s sensible opinion regarding the shift away from this type of product, the article effectively sets up a second authenticity claim. Lego has a duty to keep its sets composed of mainly, pure, or traditional, standard bricks. The mix determining whether the ideal building experience is provided.

Once more, the case for Lego’s deterioration is attached to an unsubstantiated claim as to what the correct way to build is. Specialised pieces as a result are defined as a necessary evil. They are something Lego needs to embrace in relation to the representational needs of its marketed franchises (how else can you make a convincing R2 D2 dome), but of course there ought to be a minimization of these pieces. The rot is in Lego, and needs to be monitored at a healthy level, or so say the critics.

This is a wrong-headed way of looking at the introduction of specialised pieces. Rather than being perceived as a threat to imaginative possibilities, these pieces have been behind some of the most dynamic creative shifts in the Lego building community.

In the most simple of mathematical terms, we can see that the increase in piece types ought to equate to increased possibilities, not a reduction of them; so why the vilification of these elements? Well for a start an influx of these pieces causes a problems when it comes to us recognising what we think Lego ought to look like. Basic elements of Lego conform to a simple geometric uniformity and a primary colour range. Imagination, or precisely the imagination required to render according to these limits is lost when too many non-conforming pieces are introduced. Some of these new specialised pieces provide short cuts to the rendering techniques required of basic bricks, and with it a very specific Lego aesthetic. So,paradoxically as the artistic options increase with the variety of pieces, a certain artistry is perceived to be lost. But does this change amount to a loss of imaginative potential?

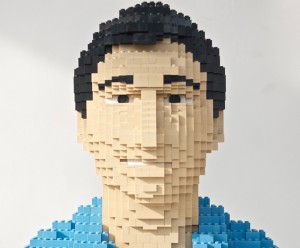

David Roberts[vii], an established builder and active member of the Lego community, was the first person to comment on my article on Lego art, he observed that the Lego that found its way into the category of art, almost exclusively was made of basic bricks. In answer I would say that the rendering skill displayed by builders such as Nathan Sawaya[viii] and Sean Kenny[ix], indeed helps their work find purchase, through the resolute veracity of its Lego geometrics. If Lego is going to be taken for art, it ought to be undeniably recognisable as such…or should it?

In reality Lego is not the stable geometric system of simple bricks that popular culture thinks it is. Rather a strange organic, constantly shifting collection of plastic shapes that connect together. From month to month different pieces are developed, or go out of circulation. Wonderful blogs such as Tim Johnson’s New Elementary[x] track all these introductions, analyse their potential for building and celebrate them. Far from being the stultification of imagination, these elements enhance, inspire and provide Lego with an ever-changing aesthetic terrain.

The imaginative potential of the specialised element can be seen writ large in the work of a builder like Mike Nieves[xi] who embraces specialised pieces. Although working in many respects in a way similar to Sawaya and Kenny, in that he seeks to render the complex through simple pieces, his selection of specialised pieces produces a stylistic shift. Much like witnessing the change in brush strokes implemented by the Impressionist painters, he alters the frame for Lego rendering. His new style, reliant as it is on specialised pieces, aligns with the arabesque rather than the expected recta-linear form of traditional bricks. And yet still, they are very much Lego creations.

What is new in the way a builder like Nieves works, is that it opens up an additional experience for the spectator. Not only do I now say, “that is made of Lego!”, but I view each piece and take pleasure in decoding its origin. In the case of Tiger V. 2[xii] by Nieves, it is found in examples such as the use of racing car driver helmets for the construction of the head. The excited mind is forced to flip between the piece’s original use and its new deployment. These new pieces as such add a new imaginative operation, not just more creative options. All of which makes it seem even more ridiculous that they have been accused of Iimiting imagination.

The art historian Christine Poggi, in her seminal study of the development of collage in Twentieth Century art, In Defiance of Painting[xiii], quotes Picasso talking to Henri Laurens in 1948 about their experiments with collage in 1914. Picasso says: ‘We must have been crazy, or cowards to abandon this! We had such magnificent means. Look how beautiful this is – not because I did it, naturally – and we had these means yet I turned back to oil paint and you to marble, It’s insane!’[xiv]. In a way the introduction of specialised pieces into the Lego range offers similar possibilities to builders as collage did to the avant-garde artists of the early Twentieth Century. And like them, we have to question why we should turn back to a time before their existence, as if the traditional brick form was a more creative approach.

Lego creations made by the selection of objects, re-appropriations of the apparently single use element for other ends, like the experiments in collage, open up a new Lego language for builders. For instance, when you look at a later sculptural construct by Picasso like Baboon and Young[xv], every child who plays with Lego will recognise the moment of inspiration where the toy car is reconfigured as the head of a Baboon.

The argument for the reduction of imagination based on the increase of specialised pieces fails because it fundamentally under-estimates a child’s or any builder’s imaginative capacity to see any piece as something else. In the Lego community this skill is referred to by the frequently used acronym NPU (nice piece usage), a useful stand in for the Lego builder’s ability to find a suitable gestalt for an unexpected piece. The talent is revered in areas like the Iron Builder contests[xvi] that pit Lego enthusiasts against each other, with the aim of finding as many applications as they can for highly specialised Lego elements. This capacity for ‘seeing-as’ means that the supposedly useless Lego croissant piece, may in fact be a crab’s claw, a strand of mermaid’s hair, a lion’s smile. We are not dictated to by the use implied in the set the piece was bought as part of. The new piece always offers fresh opportunities and the expansion of imaginative potential.

I have left the final argument that Lego fails to support the development of young scientists, to last, because it seems on first inspection to contradict the previous two cases. However it will quickly become apparent that it shares the underlying fault with the two previously examined discussions: that it too perceives there to be an ideal or authentic way of building, and Lego’s failure has been in not advocating this. Parkinson makes this case based on statements quoted from the Nobel Prize winning chemist Sir Harry Kroto, who believe that Lego has an ideal application, which it is fundamentally ill equipped to deal with. This being to provide an educational building system for young scientists and engineers to learn from. He is quoted saying: ‘Children should start with Lego, which is basically a toy, and its basic units are bricks. We do not build cars and other machines out of bricks.’

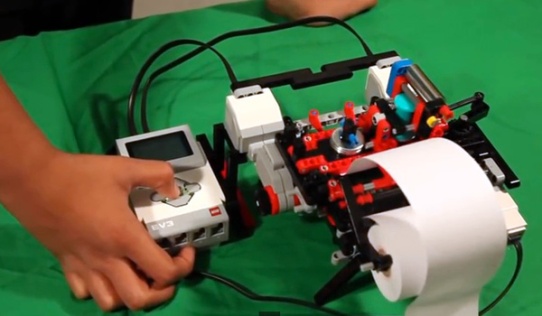

Of course Kroto is ill informed to make these comments, seemingly having not looked at the range of sets Lego is currently prodcuing. Empirical evidence stands against any claim that Lego fails to cater for the technically inspired imagination. There are the specialised ranges such as Technic and Mindstorms. Beyond this, there are thriving organisations such as Young Engineers[xvii] who use Lego (as well as other building systems) to foster children’s participation in STEM subjects. And then there is individual cases such as that of Shubham Banerjee[xviii] the 13-year old engineer who has designed and developed a low cost Braille printer with Lego.

Whilst Kroto’s ideal demands more specialised pieces, cogs, cranks, pneumatics and so forth, as well as more detailed instructions capable of teaching basic engineering skills, (the diametric opposite of the previous argued cases), ultimately there are more similarities than differences to the more culturally embedded critiques I’ve discussed. His perception of Lego’s loss of imagination is tied to linking Lego to a right way to build.

As long the critics perceive Lego according to an ideal, rather than an open system to be explored, they will bang their heads against the cases and ways it develops beyond those conditions. This is the conclusion of my analysis, that the cases against Lego’s current developments all rely perversely on a limitation of imaginative potential as a preferred alternative. They begin with untested assumptions as to what an ideal or good imaginative engagement with Lego is, and as a result fail to see the full scope of the medium. Crucially this means both accepting the reflective engagements with Lego as being as valid as the participatory ones; and that Lego’s aesthetic is not grounded in an ideal set of pieces or system of building. If you are open-minded enough to look, and really investigate what Lego is doing, and by proxy what the building community is achieving as a result, current changes are not limiting imagination rather expanding it, in unexpected and challenging ways.

Endnotes

[i] Justin Parkinson, ‘Has the imagination disappeared from Lego?’ BBC (26 November 2014) http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-29992974 (accessed 11 January 2015).

[ii] Chris Swan, ‘The Perils of Modern Lego’ Chris Swan’s Weblog (26 November 2014) http://blog.thestateofme.com/2013/01/01/the-perils-of-modern-lego/ (accessed 11 January 2015).

[iii] Swan notes on the update to his Blog following Parkinson’s article: ‘I’m very pleased that this post has been referenced by Justin Parkinson’s piece on the BBC News site ‘Has the imagination disappeared from Lego?‘, but I fear he may have misunderstood (or misrepresented) what I say about instructions. […] TL;DR – instructions aren’t the problem, they’re a good and necessary part of all sets beyond basic boxes of bricks, the problem is sets that only make one thing (like a dragon or something licensed from a movie).’ Ibid Chris Swan’s Weblog.

[iv] The LEGO Movie, dir Phil Lord and Christopher Miller, (Fox Studios 2014).

[v] Jon Blackford, Command Centre Layout 1, John Blackford’s Flickr Stream (9 February 2014) https://www.flickr.com/photos/heiwa71/12414091355/ (accessed 11 January 2015).

[vi] David Alexander Smith, ‘Building a case for Lego art’, Building Debates (3 January 2015) https://buildingdebates.wordpress.com/ (accessed 11 January 2015).

[vii] See David Robert’s Flickr stream https://www.flickr.com/photos/davidroberts01341/16252552785/.

[viii] See Nathan Sawaya’s website, http://brickartist.com/.

[ix] See Sean Kenny’s website, http://www.seankenney.com/.

[x] See the New Elementary http://www.newelementary.com/.

[xi] See Mike Nieves’ Flickr stream https://www.flickr.com/photos/retinence/.

[xii] Mike Nieves, Tiger V 2, Mike Nieves’ Flickr stream (12 April 2012). https://www.flickr.com/photos/retinence/ (accessed 11 January 2012).

[xiii] Christine Poggi, In Defiance of Painting: Cubism, Futurism and the Invention of Collage, Yale Universiy Press, New Haven/London (1992)

[xiv] Ibid, In Defiance of Painting, p.xvii.

[xv] Picasso, Baboon and Young, 1951, MOMA art collection. (http://www.moma.org/collection/object.php?object_id=81119).

[xvi] The Iron Builders contest is hosted by the Builders Lounge forum (http://builderslounge.proboards.com/), and a collection of creations made as part of the contest can be found in this Flickr group, https://www.flickr.com/groups/2167827@N22.

[xvii] See the Young Engineers website, http://www.young-engineers.co.uk/.

[xviii] See this article from the Business Insider, http://uk.businessinsider.com/shubham-banerjee-braigo-labs-2014-11.

Exemplary! I have to admit that I’m really quite baffled by the premise that more elements reduce imagination. Not only is it counterintuitive but also, as you have easily proven, completely wrong. I know personally that my mind races with possibilities whenever a new element is introduced, and I am certain that one hundred percent of those in the Lego community do the same. It is truly a given. I can’t imagine that a new color of oil paint is scoffed at and dismissed by painters as illegitimate by any stretch of the imagination; nor even a more reliable and easy to work compound of clay for a sculptor to nonchalantly toss out into the garden.

These arguments feel almost like a witch hunt, looking for the tiniest mote of criticism to hang an entire mode of thought falsely from. (Mr. Kroto has obviously NEVER seen a Technic set. And I have yet to NOT spy a new technique or NPU within any single build set.) Considering that six 2X4 bricks yields nearly a billion possible combinations and, in fact, just two of them can yield an infinite amount through abstract or “illegal” usage, the introduction of any new piece elevates the number of infinity exponentially. (If that can even exist!) I seriously doubt that we’ll run out of new uses or any engineering doldrums as a result. Besides, if these future engineers don’t understand the basics and fundamentals (which Lego is), they will never experiment, fail, succeed, AND progress. I have dealt with such engineers and architects in my metal working vocation and have found that there is a complete lack of trust with the materials. There is an unwillingness to push it’s limits up to the breaking point and enjoyably beyond. Instead, they rely on wrote. THESE are the future designers that lack imagination and retard us from advancing. You CANNOT build a fuel efficient, economical, high performance, high torque, clean fuel engine without knowing how the most elemental Briggs and Stratton 4-cycle lawnmower engine works. Or even a 2-cycle chainsaw for that matter, even more elemental! Perhaps these “engineers” need to sit down and build a Unimog.

Insightful yet again, David. I am in awe at how well you frame your argument and, in spite of any bias I have towards Lego, present it as it is and isn’t. (I’ve always said that arguing with a philosopher was always futile because they are always right. You are enjoyably so. Thank you.)

LikeLike

Thanks for the as always insightful response matt. I think you got where I was coming from. The piece usage issue is clearly nonsense. What confirms it for me is that when you check the MOC community, it is so rare that a specialised piece is ever used for that specific use it was designed for. Official LEGO designers seem quite happy to recycle these parts too!

Your note on illegal piece use also reminds me I have to write that post on Lego misappropriation and hybridity. Why do those mini-figures get all the fun, surely we can build something for the Playmobil set. I know just the builder to feature for this one.

You’ll also be pleased to know Lego humour is my next theme. Why is Batman funnier when rendered in Lego? I’ve got a few answers and maybe even some jokes up my sleeve.

LikeLike

Inspiring stuff, David.

As I have written before, I believe specialised elements have been around as long as the 2 x 4 brick. As a child, I was thrilled by specialised elements. I doubt that I used them in a NPU way! But I loved them-I loved owning them, looking at them and building with them.

Picking up on your thoughts about following the instructions of set designers; I remember feeling very frustrated and limited by the bricks I had as a child. There were so many times that I wanted to build, say, a red house: I would find after about three layers of red bricks that I had run out and had to move to multicoloured bricks. This lasted a little longer, but I still didn’t have enough to finish my house. So it was natural to follow the instructions and build the wonderful house that the set designers gave me the bricks to make in the first place. I think one of the inherent joys of being an adult builder is that you can finally have enough red bricks.

LikeLike

You are so right, specialised pieces are embedded in Lego’s DNA. When my brother and I were young and obsessed with Lego’s space range we used to scour the new catalogues each year, not just to wonder at the new designs, but also to spot the new elements. Pocket money was spent on the justification of how many new pieces any given set had. I’m pretty sure I tried this logic on my Mum, with the aim of obtaining a larger set than I could afford, based on how many new pieces it would add to my Lego collection. Can’t say it actually worked.

Reflecting now, I can see how important those pieces created for individual ranges were in defing unique design aesthetics (classic space being the one that always speaks to me), and by the same reasoning, I suspect the pieces that make Chima, Friends or Ultra Agents what they are will obtain this status. One of the most exciting things about Lego is its ability to expand its range and still feel absolutely like Lego.

Your tale of frustrated building based on piece shortages, I think is shared by every child who tried to build at the scale of their ambition. I recall laying out huge arrays of plates with the vision of creating I mmense space crafts, and never getting past the foundation stages. The joy of being able to realise those projects as an adult, is one of the main reasons I think for finding myself on a quiet Saturday afternoon joyfully putting that large selection of trans yellow windscreens to good use. However, I still don’t have quite enough black sloped bricks.

The bad press castle sets got with the introduction of their large wall pieces is one of the craziest complaints against specialised pieces i pie heard. My brother got the Lion Knights castle, and it was amazing for the simple reason that it provided us with enough elements to actually build different castles. Wen you are a child and you get a castle set, building castles is what you want todo. Sure AFOL model makers will always value the detail brick built walls provide, but for facilitating a child’s building potential, those specialist pieces were a stroke of genius.

LikeLike

I have to say that bit about “Lego is too simplistic and doesn’t help a child develop their building towards an ideal form, primarily with engineering and scientific application” Is totally wrong. I’ve built with Lego since I was four, now I’m majoring in engineering right now because I love to create new things. The creativity of Lego, for me, is certainly still alive and well. Great job on these posts!

LikeLike

I agree entirely. Lego is fundamentally too versatile to be tied to a single authenticity claim. It also offers a very diverse and interesting community. I found my way into art, I think in no small part to the way I used Lego as a child, and I get to mix with people who consider themselves designers, engineers, architects and call Lego a foundational part of their development as well. And we all share the same love of these bricks. There is an immense amount of openness in the community as a result.

LikeLike

I really enjoyed reading this and I agree with you about the “specialized” elements. There is always more than one way to use a part.

A very good example are the minifig ice skates. They have been discovered as excellent parts to represent door handles an bigger car models some time ago. This use of the part has become so popular that on the 10242 Mini Cooper set the part has been “officially” used for the same purpose.

Another good example are the 1×2 hinge plates used as rear view mirrors on small scale car models. They have found their way into “official” sets, too!

You’ve mentioned the head of R2-D2 in your article. When the first Star Wars sets appeared, a body and a head part were needed for R2-D2. Both parts are good examples for how a seemingly “specialized” part can be used in many different ways.

But even more important for me are the new parts that have appeared the last years which have uncountable possibilities because of their rather simple and “non specialized” form.

There are parts that make constructions possible which wouldn’t work without them, like 2×2 corner plates or 1x2x1 slopes with a 1x1x2/3 cutout.

There are parts with “odd” length like 1×3 tiles, 3×3 plates, 3×3 cross plates which make it possible to leaves the limitations of “even width” designing.

There are 2×2 “double jumper” plates which make a finer “resolution” of “half a stud” possible in both directions.

There are 1×1 round tiles, parts that the whole LEGO community seems to have been waiting for.

And then there is my “new best friend” the 1x2x2/3 “half bow”. It has been around for quite a short time now, but I can’t image to build anything with a smooth form without it, anymore.

Take a look at the quality of the LEGO creations that are published on MOCpages, Flickr, Brickshelf and many other platforms. Without some of the new elements it wouldn’t be possible to build many of these creations. Think about building without the 1x1x2/3 “cheese wedges” – it seems almost impossible ;-)).

There are still some builders who are masters of the “old school” look with studs everywhere, but there are many who try to avoid as many studs as possible on their creations, even building completely “studless”. That wouldn’t be possible without unsing some of the newer” elements. I prefer showing a stud or two here and there, just to show everyone: “Hey, look, it’s LEGO! You can sit a minifig or mount some additional stuff on this creation if you want.” :-))

So I think that, with some “quite specialized” and even more with some “not so specialized” new parts combined with themes like Creator, Mixels and even the equally loved and hated Bionicle LEGO has become as creative as never before.

LikeLike

Well said Nils, I think

I agree with you entirely. The infectious enthusiasm with which you speak about new elements says it all really.

I think it is often forgotten how many specialised pieces were needed to make themes like Classic Space and Fabuland work as aesthetic styles. And how many ways we have all found to reinvent and reuse these parts!

Glad you enjoyed the read, and thank you so much for your thoughts.

LikeLike

Lego sets often introduce alternative piece usages as well.

LikeLike