Jonathan Jones writing in the Guardian[i] on Nathan Sawaya’s recent touring exhibition The Art of the Brick[ii] says that ‘Sawaya’s Lego statues are interesting, but the people calling them art are missing the point. Lego doesn’t need to be art.’ It’s a valid position, but one that begs the response, is Jones missing the point? Jones confuses the argument as to who chooses what is culturally validated as art, with the argument as to what constitutes something as art. In one sense he is right, Lego creations don’t need to emulate the works found in galleries, but in another wrong, in that just because Lego doesn’t often look like so-called gallery art, or even if it does by way of a disguise (Jones’ position on Sawaya), this doesn’t mean it isn’t art.

His concluding remarks from the same article develops the point rhetorically, by asking every parent who views their child’s Lego creations, to ask, is this art? He argues this is patently ridiculous; this isn’t art, this is play; this is a toy. Because not every Lego creation is a work of art, does it follow that Lego is not an artistic medium? Jones implies that the galleries and hipsters appropriating this toy as art are missing all the fun. But is this true? There are a number of issues with Jones’ argument.

Let’s ask ourselves this: Is every child’s attempt to play Three Blind Mice on a recorder art? Is every school play performance an expression of dramatic form? Is every scribble pinned by a loving parent to the front of the fridge a masterpiece? Playing devil’s advocate, we could argue along with Jones, that just like a child’s Lego creation these too are not art, belonging to the era of play. However, the logic of the second part of Jones’ argument falters when applied to these more traditional artistic types. Because children explore music, theatre and painting in their play, it does not follow that they are excluded as mediums for artistic expression, at the highest level, later in life.

I would take a further step: childhood expression, born in the fervour of play, is still art. It may not conform to the complexity of work found in galleries, nor communicate as successfully to as broad an audience. Its context is limited to the world and life experience of the child, and their nascent skills, but it is still very much art. Talking autobiographically, as a student who studied fine art and who now works in a Drama Department in a university, on rediscovering Lego through my children, I also discovered how much of my artistic foundation began in the hours spent pushing these little pieces of plastic together.

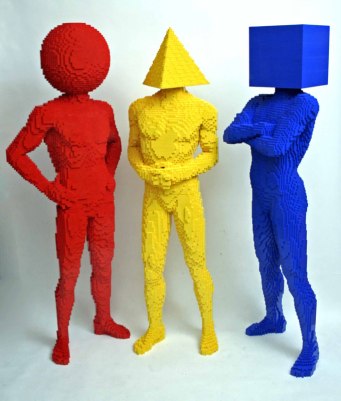

Jones’ backhanded compliments to Sawaya come from the assumption that his Lego art is in the gallery simply because it looks like the type of work one would expect to find here. Sawaya’s pieces are resonant of Antony Gormley’s figurative pieces[iii], rather than being something unique, in the fact that they are made of Lego. Give up the pretension of being art, and be Lego, be awesome, Jones says. But, is this all there is to Sawaya’s work, a wondrous manipulation of bricks that seduces us with its playfulness. That and a sense that his figures might just look enough like art to have found a way into the gallery?

Jones misses the point because he doesn’t ask the most pressing question; what is it explicitly about art that is made of Lego that makes it different from other artistic mediums? Instead he relies on all our shared experiences, normally our first experiences of Lego, as a toy, and suggests, that at best Lego in a gallery can reawaken the nostalgia we all feel for a distant childhood, for a time when we could play freely.

Before I go on to try to answer the question that Jones evades: what is unique to art works created from Lego bricks, I want to point out a few of the reasons why this question has not been seriously tackled. The major problem is that Lego was first conceived of as a toy. As a result it has no heritage as a valid artistic medium and no equivalent concept of the Academy. And as a toy it has established its genres of expression in the games of childhood, dolls’ houses, model towns and vehicles, science fiction and recently massive media franchises with Hollywood films aimed at children. This has instituted a preconception, typically based on the Lego we were given as children and the things we made with it, as to what Lego can be. It is these shared cultural contexts that produces the association that Lego is hermetically linked to play and childhood.

This position has become further embedded with the development of the adult Lego hobby scene. Many of the most active participants in this community take the themes of childhood Lego sets and present them afresh at a technically sophisticated level. The builders of spaceships making creations more akin to science fiction illustrators or the model builders of Industrial Light and Magic[iv]. Those simple model towns now share more with the architectural models of professional town planners than nursery building blocks.

Whilst often stunning, this mix of highly developed building and a love of popular culture, holds Lego back from serious aesthetic consideration in academic circles. To add to the complexity of this issue, the Lego themes of yesteryear, Classic Space, Classic Castle, and so on, have attained their own status as popular culture[v]. When Lego’s own history becomes one inextricably linked with popular culture, it becomes ever more difficult to see it as a medium, which does not necessarily have to operate within the boundaries of the popular cultural forms it is sold as.

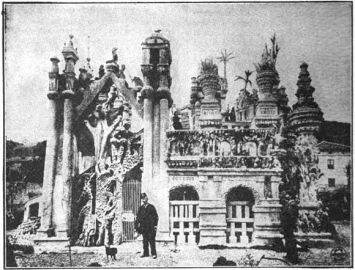

The view of the adult Lego community as a result has attained a status similar to that of a hyper-capitalist[vi], folk or outsider art. The participants although having creative skill and imagination are not trained as artists. Their expression is rather intuitive and culturally based. If you take the archetypal adult fan of Lego as represented by Will Ferrell in The LEGO Movie[vii], there are many similarities one might draw between the business man who finds an outlet for his creative expression in his basement Lego town and the type of driven creative impulse shown in the outsider artist Ferdinand Cheval’s Le Palais ideal[viii] – a vast concrete and stone palace built by hand just outside his home town of Châteauneuf-de-Galaure. When commentators have tried to speak about Lego as a creative form, it has become first and foremost a cultural phenomenon, explained by a new exposition of folk art need, founded on the experience of childhood play and a shared artistic practice found in a simple child’s toy. The movement has gained momentum in an era where the traditional working class crafts of sign painting, needlework and folk song have ceased to find purchase.

Will Ferrell in The LEGO Movie

Ferdinand Cheval, Le Palais ideal

This idea of Lego as a shared cultural form, has been explored by the artist Olafur Eliasson in his The cubic structural evolution project (2004)[ix]. Eliasson is an artist who works in many forms, normally on large installation scale pieces, however, in this particular instance he chose to work with thousands of white Lego bricks. The installation is currently being displayed at the Auckland Art Gallery Toio Tãmaki, and asks visitors to build freely with the bricks, which are scattered across a 12-meter long table. The result is a shifting shared structural form that is broken down and constantly rebuilt during the time of its display. The artist’s choice of the singular colour provides uniformity to the build, which aims to express an accessible culturally artistic medium and allow the production of evolving collaborative forms to be realised. The work has much to say about the innate creative potential we all have, and also the extent to which the simple concept of building with Lego has settled into our shared cultural identity.

Whilst this fascinating work of art uses Lego as a cipher for cultural creative expression, it doesn’t help us further an understanding ofhow Lego as a medium differs from other sculptural forms. Returning to Sawaya, in many ways his works seem far more familiar and conservative than Eliasson’s project. Certainly his works cannot be explained through the ideas of shared cultural practice, although his audience might.

A third artist working with Lego provides some clues as to how this question could be approached. Jan Vormann in a project he has titled Dispatchworks[x] has over a number of years travelled the globe, using Lego bricks to repair parts of crumbling walls and buildings; and an invitation given to anyone who wants to, to join him in this work. The result is a strange juxtaposition between traditional bricks and mortar and the brightly coloured patchwork of Lego filler. What is interesting in this process is the relationship we find between the buildings and walls we normally read as singular objects and the ephemeral status of the Lego brick. Lego constructions innately imply their own construction from parts, but equally their ability to be dissembled and reassembled as something new. The certainty of man-made architectural forms as ‘things’ is challenged by the presence of the Lego brick, which reminds us of the temporality of these structures,as well as the redeployment of their constituent parts. By allowing people a chance to imbue their serious grey cityscapes with this colourful and playful practice of building with Lego, Vormann marries the sense of communal activity and fun associated with Lego, to a particular cognitive process associated with the brick, that allows them to see their world afresh.

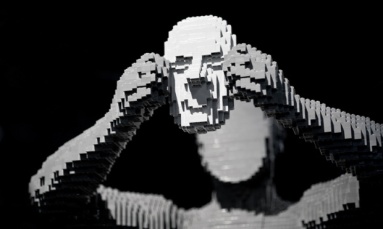

Here is an answer to the question what is unique to the work of art made of Lego? Lego always presents itself in two states: we see the basic elements thathave been composed to make it, and the complex form that still announces its origin in these basic elements. Lego constructions wear the elements of their composition on their sleeve in such a way that you cannot see the unified whole and recognise it as Lego, without simultaneously recognising that it is a construct of basic elements that can be redeployed in different ways. The wonder and joy we find in Lego art comes from the thought processes we go through in realising both of these conflicting states in the same object.

A Lego aesthetic can be taken right back to a classic problem of Seventeenth Century rationalist philosophy. Leibniz the German philosopher in a letter to his friend and fellow philosopher Arnauld on the 30 April 1687, debates the problem of substance, in terms of things which have a unified substance, and those which remain simply aggregates of other substances.[xi] A pile of stones is an aggregate of stones and can be dissembled back into its individual elements, whereas a person is a combined unity of things, which is understood as a whole, and cannot be dissembled into basic substances.

Taking Leibniz’s argument out of the context of the debate it was intended for, the universality of Descartes’ conception of substance, it provides a useful way of approaching how we think of the construct we call a work of art, and more specifically a work of art made of Lego.

Normally we are used to an artist disguising the elements that make up their works of art; as a result we read these creations as unified wholes. Only under analysis are the structural forms of for example language, musical notations or brush strokes revealed. For a work of Lego art, things are quite different. The aggregated form of the work is always announced and is in fact essential to the work being a work made of Lego. As a viewer of a work of Lego art one is always aware that it has been built from individual elements, and could in fact be returned to these basic parts. In this process the viewer is constantly made aware of the power of their own imagination, that they can see in a work’s aggregated basic elements unified forms. Equally they are made aware of the artist’s own imagination in realising this composition. The strange paradox found in the wonder of imagination experienced when viewing a work of Lego is that it also always forces imagination to fail. Because the work always presents itself as an aggregate of elements, it wrong foots imagination, forcing it to simultaneously see the uncreated pile of plastic. This foil keeps open the speculative possibility of our imagination to unify the elements into coherent wholes. This duplicity explains the unique nature of a Lego work of art, in the ability to persistently activate the power of creative imagination in all of us by constantly presenting its aggregated state.

Understanding this simple process helps us to make sense of the two most common responses people make when confronted by a Lego work of art. One I would define in terms of a work’s ability to dissimulate, the other in a work’s veracity.

It is incredibly common when viewing a hugely complex piece of Lego art, to exclaim, “I can’t believe that’s Lego.” These Lego artworks seek to dissimulate and hide their aggregated nature by hiding the individual components of their construction. However despite the aim to dissimulate, they actually work as art when their aggregate composition is revealed. The discovery that the unified object is in fact a pile of bricks is the moment when we become aware of the power of imagination required to realise it, by both the artist and ourselves. The more successful the dissimulation is, the more powerful the realisation of wonder and the power of imagination experienced when the work gives up its disguise.

At the other end of the scale, a work of Lego art may represent something we are familiar with in another context, a building, a figure from popular culture or even everyday objects, but do so with veracity to the fact that it is Lego. We respond by saying look at this or that thing made in Lego with a sense of wonder implied. In these instances, not only is the power of imagination felt in our ability to comprehend the Lego creation as a unified whole, but also in the fact that it operates at a subtextual level to disclose the unannounced use of imagination we initiate to make sense of our everyday world.

Returning to Sawaya’s work having established the cognitive cartwheels artworks made of Lego puts us through, we can answer the question Jones was unable to. Yes, Sawaya’s figures do create a sense of wonder and the feeling of play experienced when the imagination is activated, but they do more than this. By choosing the unity of the subject, and the idea of a person and the constituent problems of identity this involves, the process of imagination required to maintain the unified image of Sawaya’s figures against the aggregate composition, attains an existential significance that could only be achieved by being built in Lego bricks. The images of the subject, here, even in their coherent forms, expose the disunity of the self, and the significance of the play of creative imagination needed to create our conception of identity. Sawaya’s works have made their way into the gallery, not just because they present a spectacle of Lego building skill, but also because they marry the process of viewing Lego as art with a cognitive process that resonates with the questions he is asking regarding what it means to be a person.

The future of Lego as a recognised art form begins from an understanding of how it operates as an art form, something, which requires a more serious analysis than the journalistic appraisal that files it under fun and cultural novelty. There are already a host of talented builders out there in the Lego community pushing at the barriers of both technical skill and content for Lego creations. Mike Doyle’s curatorial project Beautiful LEGO[xii] is already starting to pull together the very best of this talent and present it in a form that unabashedly calls itself art.

Doyle being interviewed on the Lego podcast Beyond the Brick[xiii] ahead of the release of the second volume of his Beautiful LEGO series gave perhaps the clearest insight as to how the very best builders are starting to consider the relationship between Lego as a medium and the content it can deliver. Doyle announced his current project, a political response to the practice of mountaintop removal, a devastating mining technique currently being implemented in the USA. By rendering this practice in Lego bricks, he will potentially force the viewer to imagine the mountain, as the miners do, as an aggregate of resources to be exploited. The battle in the imagination between the useful pieces and the unified image replicates the societal struggle we make between respecting and exploiting our environment. By aligning this particular debate with the medium of Lego, Doyle is proposing a work which makes us not only realise, but carry out an intellectual struggle in our viewing of the work, which practically demonstrates the problem of seeing the work as both a representation of nature and the standing reserve[xiv] of bricks it is formed of.

Artists like Doyle and Sawaya are rapidly changing the perception of Lego as an artistic medium and utilising specifically its unique features to explore issues which only a few years ago would have been unthinkable. If Sawaya’s recent gallery success and Doyle’s publications are currently seen as novelty projects, which expose the versatility of Lego, in the future they may well be remembered as the forerunners of a new artistic medium and a cultural rethinking of what constitutes serious art.

Endnotes

[i] Jonathan Jones, ‘Bricking It: Is Lego Art?’, Guardian (2014) http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/jonathanjonesblog/2014/sep/23/is-lego-art-creative-play-sculpture-nathan-sawaya (accessed 29 December 2014)

[ii] Nathan Sawaya, The Art of the Brick, Old Truman Brewery Gallery, London, United Kingdom, September 26, 2014

[iii] See the homepage of Antony Gormley: http://www.antonygormley.com/

[iv] See the homepage of Industrial Light and Music: http://www.ilm.com/

[v] See for example the retrospective mythology created by Peter Reid and Tim Goddard in their Lego Space: Building the Future, No Starch Press, San Francisco, 2013

[vi] A folk art that is maintained because it is linked to an insatiable consumer habit – the Lego enthusiast can never have enough bricks.

[vii] The LEGO Movie, dir Phil Lord and Christopher Miller, (Fox Studios 2014)

[viii] Ferdinand Cheval, Le Palais ideal, Châteauneuf-de-Galaure, 1879-1924

[ix] Olafur Eliasson, The cubic structural evolution project (2004)

[x] Jan Vormann, Dispatchworks, http://www.janvormann.com/testbild/dispatchwork/ (accessed 29 December 2014)

[xi] G. W. Leibniz, ‘Correspondence with Arnauld 1686-1690) in Philosophical Texts, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1998, p.123

[xii] Mike Doyle: Beautiful LEGO, No Starch Press, San Francisco, 2014

[xiii] Beyond the Brick: Episode 139: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WcpNchpBu28&index=4&list=PLdoWYTc3JobHRJDRTIVVk2LHhMqH8XMub (Accessed 29 December 2014)

[xiv] Standing reserve is a term used by the German philosopher Martin Heidegger in his 1954 essay ‘The Question Concerning Technology’, and is used to differentiate between human instrumental use of nature and nature as being. Martin Heidegger, The Question Concerning Technology and Other Writings, Harper, London, 1977

Thanks to matt and Tim for their input and support.

Thank you for that David: I really enjoyed it. It was like going to a good restaurant and eating a tasty and interesting meal. I think that the nub of your article is, “Lego always presents itself in two states: we see the basic elements that have been composed to make it, and the complex form that still announces its origin in these basic elements.” Strangely, I can use masonry paint to paint my house for the very functional reason of protecting it from the weather. I can also use it to paint something where I might try to express and emotion or political idea but because there’s a social history of people using paint for this, no one would think to comment on the materials involved. Paint is paint.

Coming from a science/engineering background, Lego art seems to me to be similar to the idea of how we view photons and the whole wave/particle duality thing that I did in A-level physics. Look at Lego art with one filter and it’s a novel use of a child’s toy, perhaps with some interesting building techniques for the connoisseur, AFOL. The shear quantity of matching coloured bricks is a novel and perhaps distracting aspect of Sawaya’s work, for both the Lego fans and the general public. At the same time, the same plastic bricks have been used to express an idea, just like my painting in masonry paint. The two ideas seem to constantly flip states but I think that in mine and many other peoples’ brains they can’t both exist at the same time. Depending on what tools you use to view the works or what mindset you bring, determines what you see, just like trying to pin down what a photon is.

One interesting feature of the model building scene, on sites such as Flickr and MOCpages, is how much we often strive to use techniques such as SNOT to make it look like our builds are not made from Lego at all. I suppose that this is helped by the huge range of Lego parts that are not bricks, which are now available. Interestingly, the first three artists that you cite just use the basic bricks. I wonder if this is a conscious decision on their part to make sure that the audience knows that they are working in the medium of Lego?

Thanks again for an interesting, enjoyable and thought provoking read. I hope that this is the first of many!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for being the first to comment on my new blog David, it is much appreciated.

I think your paint analogy is spot on, the only difference is that the cultural assessments of Lego never rely on the case of utility to define its difference from art. Play, being much closer to art than utility has caused a quite nuanced problem. Add to this the issue of Lego as a business and you have a quite complicated set of issues to navigate when asking whether Lego can be art. Certainly there is room for an extended post on this theme alone.

Also, I think you may have been reading my mind, as piece usage will indeed be the topic of my next post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Outstanding, top shelf explanation of the deconstruction of Art by itself regardless of the medium utilized. I have studied Art my entire life while playing with Lego as a three dimensional sketchpad. It wasn’t until recently that the permanent realization that the sketches were the Art that I understood was the actual communication I was creating with others and myself. The fact that I played in the mud and sand as a child didn’t detract from the clay sculptures I created later as to their validity. Neither did the crayon drawings remove any soundness to the paintings of exploration and interpretation with purpose and intent. The added bonus of a cultural icon elevates the Art to a more inclusive level, a sort of collective conscious of recognition and tactile identity.

Art will always be a deconstructive communication. With Lego as the medium, it can be universally approachable. Seeing that the combination of six 2X4 bricks yields nearly one billion possible combinations, the potential for imaginative interpretation will follow that each one of us on this planet will find at least two of them to communicate an idea with the rest of us and, more importantly, themselves. Just because it also happens to be fun doesn’t preclude that it is no longer valid. And for that matter, you may have to explore exactly what “fun” is when the creative process takes hold and evolves into that restless, relentless, and insatiable beast.

Again, an outstanding response to Mr. Jones’ flippant dismissal of a medium that escapes his logic. I look forward to your future articles and necessary responses to help elevate Lego to its rightful place as a wonderful medium to express our shared human condition in Art.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks matt for the response here, and for the comments and encouragement you offered as I put this together. I empathise a great deal with you, as the role Lego played in my childhood was as important as the experiments I made with crayons, and notebooks full of stories I’d write. Lego was there at the start of my artistic journey and I’m happy to find it still there. And I certainly don’t feel I leave my art training or my philosophical study at the door, simply because on occasion I put my books and brushes down and pick up little plastic bricks. I look forward to your comments on the issues I’m planning to write over the next few months.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This was a fascinating article! I’m not very familiar with the AFOL community, as I’ve only been an adult for a couple of years, or with the academic art community, I’ve always liked art, but my studies have mainly focused on the physical sciences. That being said, this was an eye-opener. Even though I’ve seen many large-scale LEGO constructs everywhere from my brothers’ regional scouting pow-wow to the mall to the art gallery, I’ve always thought more about the time, talent, and creativity that went into building something so large rather than its artistic merit. While a lot of the discussion of what makes LEGO unique as an art medium went of my head, I think I got the gist of it: LEGO is different because it is both one thing and many things at once. Technically, this could be said of many art forms: a painting looks like one thing but is really thousands of brushstrokes of paint; a clay sculpture is really millions of small cemented sediments formed into a recognizable shape; etc. The difference with LEGO is it’s proud of its components. It flaunts the fact that its made up of little plastic bricks, and I think that is what’s most appealing about it to me.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for the comment and I’m glad you found the post interesting. You are pretty much there with regard to what I was trying to say. Because of the innate capacity for Lego bricks to be assembled and disassembled as a quality of the medium, our imagination is activated to recognise this. A painting or a ceramic sculpture doesn’t present itself as something that can be un-painted or un-sculpted if you like, and therefore activates the imagination in different ways. My next post is going to look at bit closer at this question of imagination, I hope you drop by and take a look when it is ready.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Developmentality and commented:

A long but interesting read about LEGO as art. I see parallels with the arguments about whether or not video games are/can be art (see e.g. http://www.rogerebert.com/rogers-journal/video-games-can-never-be-art)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the link. I’m actually very interested in the debates relating to video games as an art form. For a while now I’ve been thinking about writing something on the notion of virtuosity in video games. That like a dancer, actor or musician you can play a game in a way that displays virtuosity. A peculiar notion I know, but you could argue that an elegant, swift and seamless player of Destiny, may share a lot with the concert pianist. It helps explain the rise of streaming services like Twitch etc., that there are actually some players who are more enjoyable to watch. So whilst there are a number of good arguments abounding about the way games are made, narrative form, and links to film making and so forth, if you truly want to explain the medium, you have to also incorporate a logic that encompasses the participatory and interactive element of the player. If computer games are partly like a sport and and an art form, maybe there is a correspondence to something like ice skating, which has aesthetic form, skill, virtuosity and often a competitive edge. What is truly unique in video games, I believe, is when you start talking about the virtuosity of performance, to literally play a role with skill in a narrative driven game, especially when there is a competitive/team sport element as you find in MMORPGs.

LikeLike

I thought for those of you that follow the blog, it might be interesting for you top see Mike Doyle’s Mountaintop Removal build now it is finished: https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=336339746561469&set=a.125901007605345.1073741829.100005563386348&type=1&theater

LikeLike

Very happy to have discovered your blog, David, thanks to your MOCpage post. It’s a very well written article, and very clear, even for my limited english – I won’t pretend I’ve understand 100 % though… sadly, in france, the AFOL community don’t have such high philosophical debates – it’s all about how to get sets at a discount price, and how cool are the new minifigs.

So… what could I add which would be interesting ? Again, it’s a bit complicated for me to express complicated ideas in english, so I’ll keep things simple. Those discussions about Art and Lego are wonderful, but they might focus too much on a certain area of Lego building. While Sawaya – or Doyle – are people for who I have the most deep respect, I’m not sure that their somewhat obvious artistic works are the only ones to be interesting. The message – which is a crucial component of an artwork – might not only be in only one individual work, or in the obvious “spiritual” direction of the artist. Let me be pretentious, in a way, for a while : I totally think my own work is art. Okay, it’s very, very pretentious maybe – But ! As a lot of people who will see in my work only a collection of colorful toys, I think they miss the point. There’s actually a kind of message, too. And it’s quite simple : someone who imagine a thousand way of leaving this Earth in a futuristic manner … does he love to live here and now ? It’s the basic message also carried by our beloved sci-fi illustrators : life on this little, overpolluted, meaningless planet, is a sad joke. And, as the mighty space-rock band Hawkwind sung in the 70’s, it’s “Time We Left This World Today” ! Is that less important and meaningfull that the questions explored by the artist you’ve mentionned ?

Okay, sorry for this – maybe unclear – time of self-propaganda ^^, I just took my personnal example to show that the more basic “toys MOCs”, while being regarded by the general public – and a lot of AFOLs too, as something childish and unartistic, can actually carry something as deep and artistic than any works by the “Great Names” like Sawaya – I don’t speak for myself, but for this particular direction (which is only an example)

There’s in fact a ton of Lego fields that are just as artistic and “important”, by example the many great Lego comics (Tranquility Base, and LIU Atlas spring to mind, the later being the Lego equivalent of the Matt Groening of “Futurama”, but with this extra layer of meaning brought by this particular medium that is Lego, and that you explain so well in this article)

Well, well, well. Forget about all that. I’m just happy to have found such an interesting place ! Hope you’ll publish more great articles in the future – and keep building your own Lego art creations 😉

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for your thoughtful reply. I am in full agreement with you regarding the breadth of what can be considered art. In this article I took those individuals who are calling to be accepted by the art establishment as my case studies; they are in my mind undoubtably artists. Proving in these cases that Lego can be art opens up a way of looking at the full range of building out there in the community. Step one had to be to define the medium according to its own unique aesthetic characteristics; to emphatically prove it is not a simple copy of other art forms.

One of my planned articles actually hopes to look at Lego and science fiction. I find in literary circles the reappraisal of the genre, through writers like Darko Suvin, very interesting. Applying some of these ideas to science fiction builds realised in Lego could be exciting.

And for the record I’ve always considered your creations art, and I’m glad you do to. The snippet of ‘pretentiousness ‘ you provided really isn’t pretentious at all – more heartfelt.

LikeLike

Thanks for the kind answer ! As you’ve guessed, my answer was just trying to expand a little the subject (it was “just my two cents” as we say), but it was crystal clear to me that you choose the right direction and examples for a first article about Lego and art !

LikeLike

Fascinating! Lego is so incredibly versatile as a material, I’d have to agree that much of it qualifies as art, one way or another. Maybe not a Clone on a plate, but what you do with your negative space/light/shadow builds for sure, Sean Kenney’s sculptures, Crimso’s color/design work, Xeno’s Spiderman of loose pieces (remember that one?), and on and on. All Lego, but that’s about all they have in common. I’d also offer that the photography of Lego is a big part of this, too, especially with the online community. For example, what I built for SHIPtember, sitting on my dining room table: Is that art, or just a big ship? But editing the photo into a space scene, with the lighting and all that? Sure, why not! There’s also got the graphic design factor, like the Mertz Brothers, or Peter Mowry and his work. Unfortunately Lego can be dismissed as simply a toy, but I’d put it up against a Campbell’s Tomato Soup can any day. ; )

LikeLiked by 1 person

The problem arises from how society now defines art; the term is almost exclusively used to mean that which is deemed worthy by a cultural elite. When you look back, as I do (I know I’m a sad case), you find in taxonomies of art from the past, and here I’m thinking about the division of the arts in Kant’s Critique of Judgment, a whole host of practices being deemed different forms of art. This seems to have been lost in recent times as a way of thinking about art.

For example, it is strange that on one hand art means a certain type of film, book, dance, etc., and on the other excludes certain types of films, books and dancing. And then we call sports stars or chefs artists – how do you square that one? I guess what I’m saying in these articles is that a case like Lego can take us back to thinking about what those activities called art are. Me being the populist believes that artistic practice is far more wide-spread and successful than media and convention would suggest. Folk art is very much alive and well.

Your example that a Clone on a plate may not be art also opens up the other argument I wanted to investigate. Art is normally used as a way of defining good creative practice; bad creative practice simply isn’t art. I would disagree, a Clone on a plate is art, just very uninteresting and not very successful art. You can argue that all Lego building whether it be a child’s (or Chris Phipson’s) first Duplo stack or one of Mike Doyle’s houses is art. But the very best Lego creations, can compete with the complexity and innovation of say an acclaimed film or piece of classic literature. In short the medium can never be the differential between something being or not being art, or even between being good or bad art.

Also, I like the idea of the relationship between photography and building and photo editing and building as a topic. I might just tuck that in my back pocket for later.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve just remembered, did you get to listen to Grayson Perry’s Reith Lectures on BBC Radio 4 last year? They’re were great fun but also very relevant to this topic. You can still hear them here: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b03dsk4d

In one lecture he (jokingly) defines art as anything small enough to fit into the elevator of a Manhattan apartment block as this is where the moneyed, cultural elite live (your comments in your first paragraph to Barto triggered my memory). Anything larger will never be recognised as art, so a clone-on-a-plate cold be in!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think you and I may have talked about this somewhere before. Grayson Perry is fantastic, and I really enjoyed his lectures. He has the right balance between politically motivated irreverence and genuine passion and insight on the topic of art to make him always worth listening to. In fact I might go and revisit the lectures – thanks for the handy link!

LikeLike